This is a book with an interesting history. First published around 1973, when many of the conservation issues faced by the UK’s countryside were very different from the ones faced today, it maps the attempt by the author to walk through his own ‘unofficial countryside’ – the forgotten places on the fringes of west London and along the Colne Valley where wildlife was flourishing in any tiny cracks in urbanity it could cling on to. Mabey, an acclaimed naturalist and the author of the seminal foraging bible Food for Free, soon found that a topographical approach in which he sought to describe his journey through a coherent series of locations could not work in such fragmented and accidental surroundings. Instead he decided to organise his material according to season, with substantial sections on spring, summer, autumn winter. It was a good decision.

During his notional year we follow Mabey on compelling journeys along derelict canal banks (now benefiting some 30 years later from a far more enlightened management policy), through reservoirs and abandoned docks (now often filled in and built on) and among steaming rubbish tips (now surrendering much of their contents to a newly-formed recycling industry). In these unlikely venues, and on a sewage farm to the west of Heathrow Airport that is now Terminal Five, he finds a staggering variety of plants, birds, invertebrates and other denizens of the natural world who share our living space day in, day out.

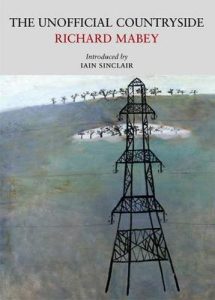

This book may be above 30 years old but the interesting thing about it is how little has changed. The pressure on land for commercial or residential development is just as strong, if not stronger and the pressure for space in our cities even more intense. This gives impetus to the decision of publisher Little Toller Books to reissue this classic in May of this year (2010) in a lovely new edition with illustrations by Mary Newcomb. And is it still worth reading? We would say it has the potential to truly change the way you view your environment whenever you’re in an urban or suburban location, sitting on a bus or train or stuck in a motorway queue.

It could lead you to discover the secrets of hundreds of species of wildlife you never even suspected of existing so closely alongside humanity. Where it does stray a little out of reach of the general enthusiast for nature and the outdoors is in Mabey’s expertise in species identification – but there are plenty of spotters’ guides out there if you find yourself with an urge to follow this aspect of the book up with some practical observations of your own. Unlike Food for Free, this is much more of a thematic investigation and it does not pretend to be a practical naturalist’s manual.

In the age of Springwatch and Autumnwatch, when thousands of people contribute photos, reports, competition answers and questions to popular nature programmes, is it likely that there is an appetite for a book like this? You bet – every bit as there is for Mr Mabey’s foraged fruit and fungi, another interest of his that has stood the test of time.